16A computational stylistic genre analysis of Spanish-American novels builds on terms and concepts from several disciplines. These must be clarified and related to each other, which is the goal of this chapter, in which genre-theoretical aspects, concepts of literary style and literary-historical basics on the Spanish-American novel are discussed. In the first part of this chapter (2.1), concepts of literary genre are approached. First, it is outlined which scholarly disciplines are concerned with genre studies, which ones are relevant for digital genre stylistics, and how they relate (2.1.1). Then three literary theoretical issues about genre, which have caused much debate in literary genre theory, are discussed, namely their ontological status and relevance (2.1.2), the relationship between systems or theories of genres and their history (2.1.3), and three main types of concepts for genres as categories – logical classes, prototype categories, and family resemblance analysis (2.1.4). All of these theoretical issues are related to digital stylistic genre analyses' practices to find out which genre theoretical concepts are useful and applicable in that field and how literary genre theory and computational genre stylistics interact. In the second main part of this chapter (2.2), a working definition of literary style is presented as a basis for analyzing metadata and text in the empirical part of the thesis. In the last part, in section 2.3, literary-historical background information is given for three major thematic subgenres and three literary currents of nineteenth-century Spanish-American novels to formulate hypotheses and establish a basis on which they can be analyzed textually.

17In general language, the term “genre” is used to designate kinds of communicative acts that may be written, spoken, or otherwise represented. Not individual instances of communicative acts are designated by the term “genre”, but the characteristics of groups of them. Genres may be of any sort of communication, for example, instruction manuals or podcasts, but in most cases, “genre” refers to forms of art such as kinds of works in the visual arts, performing arts, music, and literature, the latter being at the center of interest here, more precisely in their written form. This investigation thus focuses on literary genres.12 In a general sense, literary genres can be understood as groups of literary texts that share or can be referred to with a group name because they have something in common. For example, Agatha Christie’s “Murder on the Orient Express”, Henning Mankell’s “Innan frosten”, or Mario Vargas Llosa’s “Lituma en los Andes” can all be considered novels and, more specifically, crime novels. There has been much debate in literary studies about what the genre names are or should be, what the commonality of the texts belonging to a genre is, and what role genres play for literary texts at all. The investigation of literary genres is an old but still a central problem of literary studies, whether on a theoretical or historical level. The discussion about genres can at least be dated back to antiquity, and often, Aristotle‘s Poetics from c. 335 BCE is cited as one of the initial texts concerned with genre theory.13 Still today, there is an ongoing debate on the definition of genres both in the sense of general concepts as well as on the level of concrete individual genres, which the vast literature on genre theory and the history of genres shows.14

18However, literary genres have not only been investigated in literary studies themselves but also within the broader context of textual genres and text classes, for example, in general linguistics, computational linguistics, and information science. While in literary studies, genres are usually understood as kinds of literary works, in linguistics, they tend to be conceived as all sorts of texts, also non-literary ones, and are therefore often referred to as ”text types“.15 In the field of computational processing of text, there is a tradition, especially in computational linguistics, of describing, detecting, and distinguishing genres and types of text.16 In computer science, the task of automatically grouping different kinds of texts has been pursued under the labels of “text categorization“ or “text classification“.17 The term “categorization” is used in different ways in computer science. Sometimes it is understood as equivalent to “classification”, and in other cases, it is only used for unsupervised methods such as clustering.18 Here, in contrast, the term “categorization” is used in a more general sense to comprise all different kinds of category building. This is the sense of the term that is usually used in literary genre theory (see Müller 2010Müller, Ralph. 2010. “Kategorisieren.” In Handbuch Gattungstheorie, edited by Rüdiger Zymner, 21–23. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.).

19The concern with literary genres, the linguistic characteristics of text types, and the computational processing of text converges in digital literary studies, computational philology, or computational literary studies and more specifically in digital stylistics, or ”stylometry“. The scope of digital literary studies is broad and comprises all points of contact between literature and the computer.19 The term ”computational philology“ can also be understood as a collective term for all possible uses of the computer in literary studies, with a focus on the creation and use of digital editions, for example, but also on computational text analysis (Jannidis 2007Jannidis, Fotis. 2007. “Computerphilologie.” In Handbuch Literaturwissenschaft. Gegenstände – Konzepte – Institutionen, edited by Thomas Anz, vol. 2, Methoden und Theorien, 27–40. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.; 2010, 109Jannidis, Fotis. 2010. “Methoden der computergestützten Textanalyse.” In Methoden der literatur- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Textanalyse, edited by Ansgar Nünning and Vera Nünning, 109–132. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.). Computational literary studies, on the other hand, is a newer term for a subfield of the digital humanities in which a particular emphasis is placed on quantitative text analysis methods20. Digital stylistics, in turn, focuses on studying style with digital methods. Stylistics can be defined as “a sub-discipline of linguistics that is concerned with the systematic analysis of style in language and how this can vary according to such factors as, for example, genre, context, historical period and author” (Jeffries and McIntyre 2010, 12Jeffries, Lesley, and Daniel McIntyre. 2010. Stylistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.). The paradigmatic case of a digital stylistic study is authorship attribution, i. e. the use of statistical methods to clarify cases of anonymous or disputed authorship. However, quantitative digital methods have also recently been used for genre stylistics.21 It should be added that stylistics also is a sub-discipline of literary studies when its methods are applied and developed in the context of literary scholarship, especially because style is considered an important characteristic of literary texts (Spillner 2001Spillner, Bernd. 2001. “Stilistik.” In Grundzüge der Literaturwissenschaft, edited by Heinz Ludwig Arnold and Heinrich Detering, 234–256. 4th ed. München: dtv., 234).

20The present study, which aims to create and analyze a corpus of nineteenth-century Spanish-American novels and their subgenres, is situated in the field of quantitative digital literary studies, computational literary studies, or, more precisely, digital genre stylistics. Therefore, the theoretical discussions of genre in general literary studies are only one point of reference. Still, they constitute a central theoretical frame for analyzing literary genres in digital stylistics, and it has to be clarified which aspects of genre can be and usually are analyzed with the text analytical digital approach.

21Three issues that have been at the center of genre theoretical discussions in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are taken up here and related to questions of the design and analysis of digital corpora of literary texts in terms of genre: the question about the ontological status (are they just abstract terms or do they exist?) and the relevance of genres, the debate about the relationship between systematic descriptions and definitions of genres and their historical manifestations, and the question of the type of category that genres can be conceived as.22 These issues are considered especially relevant for literary texts and genres. They are interrelated because they all center around the question of the individuality of texts and the variability of the characteristics of text groups. The following chapters serve to address these essential literary genre theoretical issues and relate them to digital genre stylistics.

22The first of the controversial issues of twentieth-century literary genre theory that is taken up here is the question of whether genres actually exist. Another question related to it is whether genres are a relevant category for literary analysis at all because if they would not exist, why should they be investigated? Both in the early and late twentieth century, there were theoretical approaches that fundamentally questioned the relevance of genres. According to nominalistic positions, generic terms are just abstract labels to aggregate and subsume similar texts, but genres do not exist. On the other hand, representatives of realistic positions argue that genres exist independently of individual texts, for example, as psychological dispositions or anthropologically basic world views (Zipfel 2010, 213–214Zipfel, Frank. 2010. “Gattungstheorie im 20. Jahrhundert.” In Handbuch Gattungstheorie, edited by Rüdiger Zymner, 213–216. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.). In his book “Gattungstheorie. Information und Synthese”, which was published in 1973, Hempfer discusses both kinds of positions in detail by surveying a broad range of approaches that can be subsumed under the labels “nominalistic” versus “realistic”. An important early critic of considering art in terms of genre was Croce, who emphasized the uniqueness and individuality of works of art as a result of the aesthetic and creative impetus of human activity. He considers genres useless and views them as intermediate pseudo-concepts between the individual and the universal, unable to capture or describe the individual expressions (Hempfer 1973, 38–41Hempfer, Klaus W. 1973. Gattungstheorie. Information und Synthese. München: Fink.). Genre categories were also questioned later, in particular in post-structuralist theories. For example, Derrida finds that literary texts essentially break rules, while genres start from the opposite idea of a set of normative rules for text production and reception.23 Still, he indirectly also recognizes the relevance of genre for the production and reception of literary works by stating that texts participate in genres even if they cannot be neatly assigned to them:

Before going about putting a certain example to the test, I shall attempt to formulate, in a manner as elliptical, economical, and formal as possible, what I shall call the law of the law of genre. It is precisely a principle of contamination, a law of impurity, a parasitical economy. In the code of set theories, if I may use it at least figuratively, I would speak of a sort of participation without belonging—a taking part in without being part of, without having membership in a set. (Derrida 1980, 59Derrida, Jacques. 1980. “The Law of Genre.” Translated by Avital Ronell. Critical Inquiry 7 (1): 55–81.)

23According to Derrida, texts usually mark their relationship to genres, and for literature, he even sees this characteristic as necessary.24 This remark can be made consciously or unconsciously, explicitly or implicitly, it can be made relative to several different genres, and it can be made in ways undermining the referenced genre, “mendacious, false, inadequate, or ironic” (Derrida 1980, 64Derrida, Jacques. 1980. “The Law of Genre.” Translated by Avital Ronell. Critical Inquiry 7 (1): 55–81.). Frow interprets Derrida’s critique of genre as rooted in a very specific concept of it – one that relates genre to prescription and taxonomic endeavors (Frow 2015, 28Frow, John. 2015. Genre. The New Critical Idiom. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.) – but that is not without alternatives:

The conception of genre that I have been working towards here represents a shift away from an ‘Aristotelian’ model of taxonomy in which a relationship of hierarchical belonging between a class and its members predominates, to a more reflexive model in which texts are thought to use or to perform the genres by which they are shaped. (Frow 2015, 26–27Frow, John. 2015. Genre. The New Critical Idiom. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.)

24Another direction of the post-structuralist critique of genre is the one developing the concept of écriture, which was initially formulated by Barthes. He defines écriture as a level between language and style, on which authors can express themselves individually and consciously, engaging in the history of literature and pursuing social intentions. Language, in turn, is naturally given to the writers of a certain period and linguistic context, and it works as a prescriptive and habitual frame. Style, on the other hand, is an individual characteristic of each writer and is just as little controlled as the general language use (Barthes [1953] 2002, 16–18Barthes, Roland. (1953) 2002. Le Degré zero de l’écriture. Reprint, Paris: Seuil.). Compared to genre, the concept of écriture focuses more on the singularity of texts, their individual interrelationships, and the writing process. From this viewpoint, genres are seen as mere terms that suggest clear differentiations where in fact, the texts interrelate more freely and openly. In this sense, the idea of écriture is linked to recent theories of intertextuality. Nevertheless, as in Derrida’s law of genre, the genres remain a point of reference when texts allude to generic terms and conventions, be it to break them (Schmitz-Emans 2010, 107–109Schmitz-Emans, Monika. 2010. “Écriture und Gattung.” In Handbuch Gattungstheorie, edited by Rüdiger Zymner, 107–109. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.).

25On the realistic side, there are, amongst others, normative and anthropological conceptions of genre, but also communicative and semiotic approaches, including conceptualist positions.25 In general, communicative theories assume that genres exist as concepts that influence the production and reception of literary works. In a narrower sense, communicative genre theories are linguistically oriented. In a wider sense, theories that emphasize the social functions of genres can also be subsumed under this term. An influential proposition was Voßkamp’s idea to describe genres as “literary-social institutions” that undergo stabilization and dissolution processes and in which socio-historical communicative needs are condensed in a particular time and place. As such, genres are communicative models that are not mere text-internal literary phenomena but determined by a broader societal context (Voßkamp 1977, 30, 32Voßkamp, Wilhelm. 1977. “Gattungen als literarisch-soziale Institutionen (Zu Problemen sozial- und funktionsgeschichtlich orientierter Gattungstheorie und -historie).” In Textsortenlehre – Gattungsgeschichte, edited by Walter Hinck, 27–44. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer.; Zipfel 2010, 215Zipfel, Frank. 2010. “Gattungstheorie im 20. Jahrhundert.” In Handbuch Gattungstheorie, edited by Rüdiger Zymner, 213–216. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.). In semiotically oriented communicative genre theories, texts, genres, and generic terms are all conceived as complex linguistic signs, and genres can be understood as conventionalized models of an intended message or reality (Raible 1980, 324–326Raible, Wolfgang. 1980. “Was sind Gattungen? Eine Antwort aus semiotischer und textlinguistischer Sicht.” Poetica 12: 320–349.). It is assumed that such conventions and models influence authors producing literary texts and that readers, in their turn, use them to categorize and make sense of individual literary works. That way, genres become part of the communicative process and manifest themselves in it without being equated with a particular part of the process. Statements on and expectations about genres are controlled and triggered through generic signals that can accompany literary texts, be inscribed into them, and interpreted from them.

26According to Hempfer, genres are only truly communicatively and semiotically determined if they are understood as a precondition for the comprehension of literary texts that authors are forced to take into account and not only as historically possible but not necessary options of communication (Hempfer 1973, 90–92Hempfer, Klaus W. 1973. Gattungstheorie. Information und Synthese. München: Fink.). It follows from this that, communicatively speaking, literary works cannot be without genre. It does not mean, though, that every work needs to be associated with exactly one genre on one specific level. On the contrary, texts can be influenced by several genres and also on different levels of generality. The mentioned “Murder on the Orient Express” and “Lituma en los Andes” can be interpreted as instances of crime novels and, at the same time, novels and, more generally, narrative. However, “Murder on the Orient Express” can also be analyzed more specifically as a “detective novel” and “Lituma en los Andes” has also been assessed as a “novela indigenista” (Martínez Cantón 2008Martínez Cantón, Clara Isabel. 2008. “El indigenismo en la obra de Vargas Llosa.” Espéculo. Revista de estudios literarios 38. https://web.archive.org/web/20210226164843/https://webs.ucm.es/info/especulo/numero38/vllindig.html.). Then again, other texts are only framed by the genre “novel” but not a specific subtype of it. They are sometimes called “general fiction” or “literary fiction”, if the literary merit of the works is stressed.26 As Raible puts it: “Ein Werk als Exemplar einer Gattung sehen heißt es in eine Reihe von Werken stellen, die analog zu einem Präzedenzfall sind” (Raible 1980, 334Raible, Wolfgang. 1980. “Was sind Gattungen? Eine Antwort aus semiotischer und textlinguistischer Sicht.” Poetica 12: 320–349.). One work alone does not constitute a genre, but when it is produced and received according to communicative models that have formed and have been formed by other works, it becomes part of a system of generic conventions.

27If texts that participate in genres – to speak in Derrida’s terms – are understood as communicative objects, they should be described both on the level of the communicative situation and on the level of the textual sign itself. This means that both text-external features, for example, the time and place of its publication, and text-internal features, such as certain elements of content or style, determine how a text participates in a genre. Text-external factors can considerably determine a text's form, and they can narrow down the possibilities of a text's interpretation. However, literary works, especially written ones, are functionally less determined than other types of texts (Raible 1980, 334Raible, Wolfgang. 1980. “Was sind Gattungen? Eine Antwort aus semiotischer und textlinguistischer Sicht.” Poetica 12: 320–349.).

28An approach reconciling aspects of the nominalistic and realistic conceptions of genre presented so far is Hempfer’s position, which he calls “the constructivist synthesis”. Following Piaget’s theory of knowledge, on the level of scholarly description, he sees genres as structures that emerge from the interaction between the subject that seeks to understand them and the objects to which the structure is applied. These structures constitute a process of approximation between subject and object. As Hempfer formulates it:

Auf der Ebene der historischen Entwicklung lassen sich die ‘Gattungen’ nun nicht im gleichen Sinn wie etwa die Geburt Napoleons als ‘Faktum’ begreifen, sondern es handelt sich, wie in den verschiedensten semiotisch orientierten Gattungstheorien betont wird, um Normen der Kommunikation, die mehr oder weniger interiorisiert sein können. Da diese Normen aber an konkreten Texten ablesbar sind, werden sie für den Analysator zu ‘Fakten’ und lassen sich demzufolge allgemein als faits normatifs verstehen, ein Begriff, den Piaget aus der Soziologie zur Bezeichnung analoger Phänomene in die Psychologie eingeführt hat. Diesen faits normatifs wird dann in der wissenschaftlichen Analyse eine bestimmte Beschreibung zugeordnet, die als solche immer ein aus der Interaktion von Erkenntnissubjekt und zu erkennendem Objekt erwachsenes Konstrukt darstellt. (Hempfer 1973, 125Hempfer, Klaus W. 1973. Gattungstheorie. Information und Synthese. München: Fink.)

29The more interiorized the communicative norms are, the more they approach the status of ahistorical constants (for example, knowledge about what narrative is). Hempfer aims to differentiate the ahistorical constants from historical norms that are less interiorized and more subject to open (for example, poetological) discussion and change (Hempfer 1973, 126–127Hempfer, Klaus W. 1973. Gattungstheorie. Information und Synthese. München: Fink.).27

30This paper follows Hempfer’s idea that genres are not to be understood as objective facts, but as communicative phenomena that can, however, leave traces in texts. If genres are understood as norms, then such textual traces can be conceived as normative facts in Hempfer’s sense. The connection between genres as communicative norms and the texts on which they have an influence results in turn from the communicatively established assignment of texts to genres. How is it made clear that a text participates in a genre? This can be expressed, for example, through generic signals in the texts but also through signals that accompany the texts (e.g., in subtitles or paratexts). Thus, genre signals and genre names used in connection with literary works have a special significance for establishing genre affiliations. The various references and levels of meaning of such linguistic expressions of genres are broken down, in particular, in semiotic genre theories. Since genre labels are digital genre stylistics’ primary approach to communicative genre norms, semiotic genre models are discussed in more detail in the following chapter.

31One aspect that semiotic models of genres focus on is the multilayered meanings of generic terms, which point to the many communicative levels that genres can be defined on and the complexity of genres as signs. As signs, the generic terms can be understood as models for the even more complex models that the genres themselves are conceived as (Raible 1980, 334Raible, Wolfgang. 1980. “Was sind Gattungen? Eine Antwort aus semiotischer und textlinguistischer Sicht.” Poetica 12: 320–349.). Two semiotic models for generic terms are presented in more detail here. These are used as a basis for an empirically established discursive model of subgenre terms for the corpus of nineteenth-century Spanish-American novels created and analyzed in the context of this dissertation.28 The first of the two models has been formulated by Raible (1980, 342–345Raible, Wolfgang. 1980. “Was sind Gattungen? Eine Antwort aus semiotischer und textlinguistischer Sicht.” Poetica 12: 320–349.) and involves six dimensions from which generic terms usually draw their meaning and classificatory features:

Commençons par une question banale: quel est le statut des classes générique? Ou, pour éviter de nous encombrer dès le début d’entités peut-être fantomatiques, demandons-nous plutôt: quel est le statut des noms de genres? [...] l’identité d’un genre est fondamentalement celle d’un terme général identique appliqué à un certain nombre de textes. [...] les noms générique traditionnels sont la seule réalité tangible à partir de laquelle nouns en venons à postuler l’existence des classes génériques [...]. (Schaeffer 1983, 65–67Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. 1983. Qu’est-ce qu’un genre littéraire? Paris: Seuil.)

32The names of the genres are significant because they witness that a generic class of texts has a communicative existence, condensed in a name. Furthermore, names applied to texts signal that the texts participate in the genres, and the participating texts, in turn, contribute to the genre’s identity. The above quote is intentionally reduced to concentrate on the aspect of relevance of the generic names. In the wider context, Schaeffer explains that the relationship between the generic names and the texts is not at all simple. The names can have different statuses, as analytical ex-post terms, as words in use in a very specific historical situation, or as something between both of these poles. They can be applied collectively to a set of texts at once or to individual texts so that multiple applications of the terms, or their sum, form the genre. The meaning of generic names is not fixed, not synchronically, and especially not over time, and they can be related to other terms. One text can be associated with several generic names, which may involve different levels of significance (Schaeffer 1983, 65–66, 69Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. 1983. Qu’est-ce qu’un genre littéraire? Paris: Seuil.). Schaeffer emphasizes that he does not want to replace a theory of genre with a lexicological study of generic names but wants to start from them to account for the fluent character of the genres and to understand the kind of phenomena that are covered by the generic names (Schaeffer 1983, 75–76Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. 1983. Qu’est-ce qu’un genre littéraire? Paris: Seuil.). For Schaeffer, a generic term is any term, “á condition qu’il soit utilisé pour classer des œuvre ou des activités verbales linguistiquement et socialement marquées et encadrées (framed), et qui se détachent par là de l’activité langagière courante” (Schaeffer 1983, 77Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. 1983. Qu’est-ce qu’un genre littéraire? Paris: Seuil.). He thus does not start from a strict separation of generic terms for literary and non-literary works, although his study focuses on the former. A condition for a term to be generic is that it is used for classifying works or other linguistically and socially marked and situated verbal activities. This definition again focuses on the communicative function of genres. It is limited to oral and written linguistic acts because it presupposes verbal activities, which excludes, for example, communicative acts in the visual or performing arts or music. However, within the literary-linguistic frame set by Schaeffer, all kinds of generic terms are considered.

33A central observation that Schaeffer makes is that generic names do not all refer to one specific dimension of a literary work. Possible dimensions are, for example, the syntactical and semantic chain of a text that expresses a work. Instead, generic terms pick up all kinds of levels of a work as a global discursive act. That way, the generic identity of a literary work is not unique and fixed but depends on the perspective or perspectives taken towards it (Schaeffer 1983, 79–80Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. 1983. Qu’est-ce qu’un genre littéraire? Paris: Seuil.). Similar to Raible, Schaeffer defines a literary work as a complex semiotic object. He describes dimensions of this object to which generic terms usually refer. Schaeffer’s model comprises five principal dimensions:

34The approaches that view literary genres as complex semiotic objects are characterized by differentiation and openness. An advantage is that they enhance the comparability of different genres by clarifying on which discursive levels generic terms operate without restricting the functioning of genres to a specific communicative level. On the other hand, some genre theoretical aspects are not clarified by these models because they focus on the communicative nature of generic structures. For instance, the semiotic models do not include the generic terms’ provenience and their theoretical or historical nature into the core model, nor do they make statements about the kind of categories that genres can be (if they are to be understood as classes of texts, as prototypical structures, or other types of categoric relationships between literary works). Therefore, these two genre theoretical aspects are discussed further in the subchapters 2.1.3 (“System and History”) and 2.1.4 (“Categorization”).

35The focus of the semiotic models on generic names leaves out another aspect of genres: who says that there are no communicative patterns without a name? There may be genres that have not been explicitly discussed or labeled but nonetheless exist as frames for communicative acts. A sign of this is that there are genres that have primarily been labeled by literary scholars in retrospect but that were not explicitly named in their historical peak phase. This does not necessarily mean that the scholars made arbitrary classifications without considering contemporary communicative practices. For example, both the novela gauchesca and the novela indigenista could not be found as explicit generic labels in the bibliography and corpus of nineteenth-century Spanish-American novels that were prepared for this dissertation.29 They are, nonetheless, established subgenres of the novel in the corresponding literary historiography (see, for instance, Ghiano 1957Ghiano, Juan Carlos. 1957. “La novela gauchesca.” La Biblioteca, Época 2, 9 (1): 17–38. and Meléndez 1961Meléndez, Concha. 1961. La novela indianista en Hispanoamerica (1832–1889). Rio Piedras: Universidad de Puerto Rico.). Furthermore, generic signals, i.e., text-external or -internal aspects of literary works that indicate in which genres they participate, are not limited to explicit mentions of generic names. They can also be implicit or established through intertextual references (Fowler 1982, 88–105Fowler, Alastair. 1982. Kinds of Literature. An Introduction to the Theory of Genres and Modes. Oxford: Clarendon Press.). However, such indirect signals are not directly congruent with a sign-based linguistically oriented approach and thus need to be taken into account in addition.

36Up to this point, the ontological status of genres has been discussed, with a particular focus on semiotic theories of genres. In the following chapter, the general, genre-theoretical considerations will be directly related to the approaches of digital genre stylistics. Which possibilities of knowledge about genres arise from digital analyses, if they are carried out starting from certain genre-theoretical foundations? Which methodological aspects of computational genre analyses play a role in this context? Which genre theoretical approaches have been used in digital genre stylistics so far? In the following, these questions will be discussed, focusing on the special role of digital text corpora, genre labels, textual features, and text style in digital genre stylistics.

37Regarding the question of the ontological status of genres, Hempfer’s synthesis can be productively related to approaches pursued in digital genre stylistics. In digital stylistics, the anchoring point between genres as communicative norms and their descriptions in terms of textual features is just the style of the texts. Whenever literary works are associated with specific genres, a basic assumption for a digital stylistic genre analysis is the following: that the text style can be analyzed to assess to what degree there are normative facts expressing the generic participations of the works in the genres and of what these facts consist. Obviously, the analysis of text style is limited to the syntactic realization of the discursive act, but this does not mean that digital stylistic concepts of genre are reduced to this level of communication. The level on which digital genre stylistics principally operates is the linguistic, strictly speaking, even the orthographic surface of certain manifestations of literary texts as they are transmitted in a form that is determined by the digital medium. Still, many kinds of discursive aspects can be analyzed on this level. The crucial point is how the participation of the texts in genres is modeled and defined. As several literary genre theorists have pointed out, texts can be classified arbitrarily by any criterion, and this would include any computationally tractable aspect of text style.30 Such an endeavor is not the point in itself. The question is to which communicative norms of genre the texts relate and in what way. A good example of taking the relativity and significance of generic assignments into account is a study conducted by Underwood, in which he analyzes different definitions of Gothic novels at different points in time.31 As Underwood states:

Distant reading may seem to lend itself, inevitably, to literary scholar’s fixation on genre as an attribute of textual artifacts. But the real value of quantitative methods could be that they allow scholars to coordinate textual and social approaches to genre. This essay will draw one tentative connection of that kind. It approaches genre initially as a question about the history of reception — gathering lists of titles that were grouped by particular readers or institutions at particular historical moments. But it also looks beyond those titles to the texts themselves. Contemporary practices of statistical modeling allow us to put different groups of texts into dialogue with each other. (Underwood 2016, 2Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.)

38The debate that Underwood engages in is the question of the life cycle of genres. Some critics sustain that genres have relatively short life cycles, roughly corresponding to one generation and about 25 years. Others say that genres can sustain an identity over periods much longer than that, even if there are shifts in the concept of the genre. “Textual analysis won’t prove either claim wrong, but it may help us understand how they’re compatible” (Underwood 2016, 2Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.). With this assertion, Underwood outlines an important task of digital genre stylistics: not necessarily to refute or confirm claims that are made on other levels of genre investigation (as here in the history of reception), but to look for textual and more specifically stylistic evidence as traces of these other levels. That way, genres are not established in style, but through style. Underwood aims to investigate how textually coherent the Gothic is over time:

Evidence of this kind [that only a one-generational linguistic coherence could be found] wouldn’t rule out the possibility of longer-term continuity: we don’t know, after all, that books need to resemble each other textually in order to belong to the same genre. But if we did find that textual coherence was strongest over short timespans, we might conclude at least that generation-sized genres have a particular kind of coherence absent from longer-lived ones. (Underwood 2016, 3Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.)

39So digital genre stylistics can help to find out which genres imply stylistic coherence of the texts attributed to them at all and on which levels of text style they do. Underwood finds out neither strong evidence for the succession of genre generations nor for a gradual consolidation of the genres over time. The sensation novel is short-termed but textually not very coherent, while detective novels and science fiction novels are textually connected for longer periods (Underwood 2016, 4Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.).32

40If digital stylistic genre analysis functions as a connector between social and communicative norms of genre and stylistic textual evidence, several aspects in the connective chain need to be defined and selected with care. Usually, a corpus of texts is analyzed, and the generic conventions in question are expressed as genre labels of the texts, which themselves are representatives of literary works. The assignment of genre labels to the texts is the first crucial point. Which kind of genre labels are selected, and how are they assigned to the texts? The semiotic models of generic terms provide a way to differentiate between different discursive levels on which genres can be defined, which can help not to compare “apples with oranges”. That would happen if one would, for example, contrast primarily formally defined genres with thematically defined ones. The sources of the genre labels should always be indicated to document which kind of generic convention they represent. Do the genre attributions go back to assignments made to individual texts by different authors, editors, or publishers? Or are they collectively defined, for example, established in a discussion of a set of works by a contemporary critic or poet, by modern institutions, or by a literary historian? Are the assignments made based on explicit generic terms or implicit signals of the texts? Or are they derived from specific theoretical definitions of genres that are applied to the texts? Depending on the answers, quite different kinds of generic conventions can be analyzed. In the worst case, it is not clear which type of genre an analysis aims at, and the goal of addressing a communicative pattern that lies outside of the analysis itself would be missed. Awareness of the kind of analysis target can still be raised in digital genre stylistics.33 Despite all good advice and intentions to analyze genres or subgenres only on a defined discursive level or on the basis of homogeneous sources of subgenre labels, especially large-scale digital analysis using hundreds or even thousands of texts have to face challenges in defining which generic conventions they refer to. Even in qualitatively oriented genre analysis, selecting works for a corpus that aims to cover one or several specific genres is not trivial. A starting point using either certain labels or definitions of the genre(s) has to be found.34 Beyond that, some strategies of text selection and genre assignment are not viable for very large corpora. It is, for example, not possible to read every text and check it against a genre definition that relies on qualitative textual features, i.e., characteristics of the texts that are not (yet) easily formalized and computationally analyzable. Furthermore, it is very likely that large corpora also cover lesser-known texts which critics have not considered yet. That way, existing critical approaches may only cover part of a text corpus. On the other hand, depending on the kind of genre, explicit labels on historical editions may also not be the norm. These are additional difficulties that quantitative genre analysis faces in defining of its object of investigation through the selection and preparation of the text collection. Such challenges make it even more important to clarify which genre convention is addressed and how this is done.

41Besides assigning genre labels to the texts, another fundamental point for a digital genre analysis is the selection of textual features. In the end, the normative facts that can be found in the texts, that can be related to genre conventions, and that can be used to establish definitions of genres, depend on which kind of textual material is analyzed. There are different opinions regarding the importance of which kind of features are selected. Underwood, for example, highlights the predictive power of statistical models, which is based on specific features but not directly dependent on them:

Leo Breiman has emphasized that predictive models depart from familiar statistical methods (and I would add, from traditional critical procedures) by bracketing the quest to identify underlying factors that really cause and explain the phenomenon being studied. Where genre is concerned, this means that our goal is no longer to define a genre, but to find a model that can reproduce the judgements made by particular historical observers. (Underwood 2016, 5–6Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.)

42Taking the example of science fiction, Underwood explains that a very reliable textual clue for this genre are adjectives of size such as “huge” or “tiny” and that a set of some more hundred words would be enough for a statistical model to recognize instances of the genre. Still, he argues, these genre markers do not need to correspond to any definition of the genre that has been formulated so far, and they might not lead to any definition that could be articulated verbally in a useful way (Underwood 2016, 6Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.). Underwood’s stance towards selecting textual features is characterized by a reproductive strategy on the one hand and an explorative one on the other. It is a reproductive strategy in the sense that text analysis is used to replicate social constructions of genre to find out about their general relationship to the textual basis. It is explorative in that the kind of features used is not defined in a top-down approach and controlled in advance, but tested as for their reproductive relevance: “To put it more pointedly: computational methods make contemporary genre theory useful. We can dispense with fixed definitions, and base the study of genre only on the shifting practices of particular historical actors – but still produce models of genre substantive enough to compare and contrast. Since no causal power is ascribed to variables in a predictive model, the choice of features is not all-important” (6Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.). Following this approach, the normative facts found as traces of social constructs of genres would not lead to descriptions of them in scholarly terms, at least not to definitions focusing on the kinds of facts found.

43A different view on the question and relevance of feature selection is formulated by Jannidis, who outlines a set of general methodical working steps for computational text analyses: “1. Thesenbildung, 2. Bestimmung der Indikatoren, 3. Korpuszusammenstellung, 4. Korpusvorbereitung, 5. Suche, 6. Quantitative Erhebung, 7. Überprüfung von Indikatoren und Korpuszusammenstellung sowie Diskussion der These im Licht der Ergebnisse” (Jannidis 2010, 110Jannidis, Fotis. 2010. “Methoden der computergestützten Textanalyse.” In Methoden der literatur- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Textanalyse, edited by Ansgar Nünning and Vera Nünning, 109–132. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.). In this setup, the choice of indicators is directly linked to the formulation of an initial thesis and is more driven by prior theoretical assumptions than in Underwood’s approach.35 It represents a deductive procedure. In the case of genre analysis, a genre-related thesis would need to be formulated, for instance: “In social novels, there are more different characters than in sentimental novels”. To be able to verify or falsify the hypothesis through computational text analysis, it would be necessary to define textual indicators representing the concepts mentioned in the hypothesis. The above example would require an approach to identify characters in the text, for example, by detecting mentions of character names and other linguistic references to characters and resolving to which character they point. It would be necessary to automatically detect the set of different characters in a novel, which is a difficult task. Somewhat easier to formalize and closer to a stylistic analysis would be a hypothesis such as “In social novels, there are more mentions of different character names than in sentimental novels”. Like the explorative procedures, also top-down approaches have several advantages and disadvantages. What is good about them is that they start directly from the scholarly field that is also the target context. If the goal is to find out something about literary genres and the hypothesis is formulated in literary scholarly terms, the hypothesis is compatible with the epistemological frame of the investigation. In addition, the selection of textual indicators and features can be motivated theoretically so that meaningful and interpretable results can be expected. The main disadvantage is that the possibility of formalizing the hypotheses depends on the available technical methods. Although research is done in this direction, many literary theoretical concepts still need to be formalizable.36 Existing text mining methods, for example, topic modeling or sentiment analysis, may also be used to operationalize the hypotheses. Then it must be explained in what way they can be considered formalizations of literary theoretical concepts, such as themes, topoi, or emotions. In any case, in such an approach, the selection of specific textual features is not at all arbitrary or negligible. The features represent the texts and are assumed to cover stylistic aspects that are traces of generic conventions in the texts. The chosen indicators must be suited to check the plausibility of the literary theoretical hypothesis. At the same time, the choice of the indicators themselves is based on assumptions: “Das Verhältnis zwischen Indikatoren und These ist allerdings in vielen Fällen keineswegs selbstverständlich, sondern hat selbst hypothetischen Charakter” (Jannidis 2010, 116Jannidis, Fotis. 2010. “Methoden der computergestützten Textanalyse.” In Methoden der literatur- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Textanalyse, edited by Ansgar Nünning and Vera Nünning, 109–132. Stuttgart, Weimar: J.B. Metzler.). Even in hypothesis-driven digital genre analysis, the suitability of the features needs to be tested empirically to some degree.

44In the same way as the kind of generic convention that is analyzed and the selection of corresponding genre labels, the choice of textual features for a digital stylistic genre analysis should also be motivated. How specific the chosen features are and how important it is to clarify their relationship to literary theoretical concepts depends on the kind of strategy that is chosen for the genre analysis: it can be primarily deductive, inductive, or experimental, and it can be theoretically or historically oriented. In principle, digital genre analysis can be used for all kinds of investigations. The goal can be, for instance, to find out if and in what way works with specific historical or critical genre labels are textually coherent, as Underwood did. Another goal can be to test if a specific scholarly definition of a genre holds when it is formalized and applied to a corpus of texts that have been assigned to the genre in question. The results of a stylistic genre analysis could also be used to formulate new, statistically-based definitions of genres. Even if textual variables in statistical models do not necessarily reflect causal relationships, their distribution can be interpreted to reach empirically based genre definitions if genres can be distinguished based on these variables. A sentence in such a definition could be, for example, “the genre X is defined such that the probability of a love topic is significantly higher in texts that participate in the genre X than in texts that do not participate in this genre”. In Hempfer’s terms, the normative fact that was found is the different probability of a certain kind of topic in two groups of texts that are associated with different genres by convention. The genre is constructed in the interaction of the scholar who decides which textual features to use and which texts to analyze on the one side and the texts themselves on the other. Moreover, the scholar has to interpret the topics and decide that one of them can be described with the term “love”. Furthermore, it has to be decided what “significantly higher” means. A definitory phrase such as the one above can itself be used as a hypothesis that can be tested in other empirical settings, for example, with a different corpus of texts. To what extent the found textual characteristics of exemplars of different genres actually correspond to conscious social norms can only be clarified by analyzing contemporary or historical discussions about what the genres in question are. That would not be different in non-computational text analysis. In addition, besides starting from known generic conventions or scholarly definitions of genre, a digital stylistic genre analysis can also start from the texts themselves. For instance, a corpus of texts can be built for a certain period and a specific cultural, geographical, and linguistic context. It can then be analyzed which groups of texts emerge as textually coherent when specific textual features are used. Such an approach would allow for the possibility of detecting faits normatifs as signs of communicative patterns that might not have had a high degree of explicitness. They might not have been frequently named or broadly discussed in the historical context, and possibly they have not been described yet in scholarly terms. In such cases, it would as well be possible to complement the quantitative analysis with a qualitative study of intertextual links, of implicit or explicit signals in the texts and paratexts, and of metatextual statements that could substantiate or question the communicative relevance of new findings of text groups.

45When stylistic text features are interpreted as signs of generic conventions, a difficult point is how clearly the relationship between both characteristics of texts can be established: having certain features or a specific distribution of them on the one hand and participating in a particular generic convention on the other. In this context, only the causal relationship between the genre label and the textual features is meant, not the question of the kind of social, generic norms and their unconscious or conscious application. In many cases, literary-historical studies of genres focus only on one, positively described genre.37 Often subtypes of one genre are distinguished as part of the investigation, especially if a major genre is concerned,38 but explicitly contrastive studies are rare.39 In corpus-based and empirical digital genre stylistic analysis, it is more usual to directly contrast different genres or subgenres to find distinctive features for each group (see, for instance, Schöch 2018Schöch, Christof. 2018. “Zeta für die kontrastive Analyse literarischer Texte. Theorie, Implementierung, Fallstudie.” In Quantitative Ansätze in den Literatur- und Geisteswissenschaften, edited by Toni Bernhart, Marcus Willand, Sandra Richter, and Andrea Albrecht, 77–94. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110523300-004. and Schöch et al. 2018).40 Approaches based on statistical classification also bring forth features that are decisive for distinguishing different classes of texts.41 If only the characteristics of one genre are worked out, one cannot say with certainty that there are not other genres that share part of these characteristics. This possibility is avoided in contrastive studies. On the other hand, the results of comparative approaches obviously depend on what is compared. A contrastive text analysis aiming to define the sentimental novel, which is based on a corpus of sentimental, historical, and adventure novels, will lead to a definition of the sentimental novel that is relative to the other subgenres. If sentimental novels were instead compared to science fiction and crime novels, different aspects might be decisive in their distinction and recognition. The choice of the corpus that is used to determine a genre in the context of other genres is, therefore, a central aspect of digital stylistic genre analysis. In the case of contrastive analysis, the relationship between the textual features and the genre in question is established relative to other genres on which the outcomes depend.

46Another challenge in this regard is that text style is not only a function of genre. All kinds of intra- and extra-textual phenomena shape the style of a text. A special awareness of this circumstance has developed in the field of authorship attribution, where it was repeatedly noted that, for example, the period a text was written and published in but also its genre interfere with authorship signal.42 In the same way, authorship, time period, and other factors can also obscure the link of textual features to genre.43 It may thus happen that conclusions are drawn about genre that are instead due to unrecognized effects of other variables. Considering the different discursive levels on which generic terms and genres can be defined, it is also likely that these different levels may correlate or interfere with each other. For example, in the bibliography of nineteenth-century Spanish-American novels that was prepared for this dissertation, there are 172 novels with the primary thematic subgenre “novela sentimental”. For 85 of these, the literary current to which they belong is unknown. 72 have been associated with the romantic current, 15 with the realist, eight with the naturalistic, and two with the modernist current.44 Putting aside the cases of unknown literary currents, the numbers suggest a strong correlation between a primarily sentimental theme and the romantic current. Definitions of the sentimental novel derived from this set of novels will therefore be strongly influenced by the period in which the romantic current was the dominant aesthetic program.

47If there are undesired factors that influence the target style that is analyzed (e.g., the influence of period on genre style if genre is the primary concern), then several strategies are possible to cope with such factors. A crucial aspect is the construction of the text corpus that is used for the genre analysis. For example, it is possible to include only one text or an equal number of texts per author. This prevents the results from being too much influenced by authors that were very productive writers of texts that can be attributed to specific genres. However, in most cases, creating a balanced corpus means moving away from a text collection that represents the historical proportions of works according to specific criteria. It means that one tries to create a synthetic setting that can be used to get results that are free from unwanted influencing factors in order to reach a definition of the subject that is theoretically “clean”. This may be very difficult if there are not enough sources for such a corpus. Going back to the Spanish-American sentimental novels, taking an equal number of romantic and realistic sentimental novels would reduce the number of novels to analyze to 30 instead of 172. Besides controlling external factors through corpus building, another possibility is to try to choose the text features in such a way that they are likely to be relevant for specific generic distinctions but not for other kinds of differences. However, it has so far not been possible to isolate features that are only connected to a single extra- or intratextual influencing factor.45 A third way would be to model the factors that are assumed to influence the target variable, for example, by collecting corresponding metadata and using this information when the analysis results are inspected. In principle, a corpus that is created by random sampling may represent historical imbalances. However, it would still be possible to estimate how much influence other factors have on the stylistic features that are interpreted in terms of the genres that are investigated. The decision for a specific strategy to control different factors that may influence the text style may depend on the aim of the study. The wider the claim of validity is for the results that are reached, i.e., the more independent they should be from contextual determinations and intra-textual correlates, the more important it is to build a corpus and features that are theoretically adequate. The narrower the scope of the genre study, the more it will be acceptable to have a corpus and feature set that is influenced by the specific historical setting, and that leads to a less theoretical but more organic description of the genres in question. Looked at another way, the stronger the theoretical claim on the results of a corpus-based study, the more important it is to control for possible factors influencing the target variable of the study, i.e., literary genres. On the other hand, a primary interest in historical adequacy can be pursued by considering and investigating influencing factors, but not necessarily controlling them, for example, by balancing a corpus of texts. Awareness of influencing factors is still indispensable in both cases to make sure that the assertions made are about genre at all.

48It is clear that the ontological status of genres as conventions or norms of communication or social interaction – if they are understood in that way – makes the access that digital genre stylistics has to them one that is mediated by text style. Text style, in turn, is influenced by a number of factors other than genre. These influence factors are never captured as a whole but only on selected levels of textual features that are chosen for analysis. One could say that genre “hangs by a thread” for digital stylistics, but in general, in the debate about the status of genres, the field can be characterized as inclined towards the realistic side. How strong the connection between genres, genre labels, and genre signals, on the one hand, and common features of text groups, on the other hand, is, can be analyzed in detail with digital text analysis. It is to be expected that the results may be quite different depending on the kinds of genres and the literary-historical contexts that are investigated. Quantitative approaches lend themselves very well to analyzing big corpora of formula fiction, that is, popular genre fiction for which uniform patterns of style are expected. In such a research setting, genres are probably more tangible than in an analysis of highly canonized, individualistic works of art where generic references may be weaker.46 Furthermore, as was pointed out above, digital genre stylistics is a field that is closely linked to computational linguistics, and the existence of linguistic text types is less questioned than the one of literary genres, mainly because it is more evident that the text types constitute communicative norms.

49There are further aspects that are as well relevant to the relationship between literary genre theory and digital genre stylistics and that have not been covered yet in this discussion of the role of corpora, genre labels, features, and text style. One aspect is the relationship between genre systems and their history, a field of tension that is also linked to terminological questions. Another aspect is the debate about the type of categories that genres can be conceived as. These issues will be touched upon in the next chapters.

50Besides the ontological status of genres and the question of how genres are to be grasped communicatively and textually, another central point of debate in the theoretical discussions of genre in the twentieth century was about the relationship between a system of genres and their history (Zipfel 2010, 214Zipfel, Frank. 2010. “Gattungstheorie im 20. Jahrhundert.” In Handbuch Gattungstheorie, edited by Rüdiger Zymner, 213–216. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.). In this and the following chapters, major positions on this question are outlined and it is discussed how they relate to approaches of digital genre stylistics. The question involves several issues, among which are:

51There is a range of different propositions for defining the relationship between systematic and historical genre concepts. An early proposal was formulated by Todorov, who argued for the necessity to distinguish between theoretical genres that arise from deductive procedures and are based on a theory of literature and historical genres that are captured by observing the historical, literary reality. Todorov sees historical genres as a sub-ensemble of theoretical genres. That the definition of theoretical genres depends on a theory of literature is explained by Todorov as follows: a theory of literature involves a concept of how a literary work is represented. A theory of genres then refers to the theoretical concept of the literary work to determine on which levels of this concept genres are defined and which generic characteristics are available on each level. According to Todorov, three aspects must be distinguished for a representation of a work: the verbal, the syntactic, and the semantic aspect. The first one corresponds to concrete phrases of a text that represents a literary work and is connected to questions of register,47 style, and the instance enunciating or receiving the text. The second level concerns the composition of a literary work, that is, the organization of its different parts (logically, temporally, or spatially). For the third level, the semantic one, the themes or topics of the literary work are relevant (Todorov 1970, 24–25Todorov, Tzvetan. 1970. Introduction à la littérature fantastique. Paris: Seuil.). Possible theoretical genres are deducted from the constellations of characteristics that are available on the different levels that the literary work is defined on. The historical genres are a sub-ensemble of them because not all of the theoretically possible genres may be found in the history of literature. Although Todorov proposes a clear distinction between theoretical and historical genres, he also sees how they are interrelated:

Les genres que nous déduisons à partir de la théorie doivent être vérifiés sur les textes: si nos déductions ne correspondent à aucune œuvre, nous suivons une fausse piste. D’autre part, les genres que nous rencontrons dans l’histoire littéraire doivent être soumis à l’explication d’une théorie cohérente ; sinon, nous restons prisonniers de préjugés transmis de siècle en siècle [...]. La définition des genres sera donc un va-et-vient continuel entre la description des faits et la théorie en son abstraction. (Todorov 1970, 25–26Todorov, Tzvetan. 1970. Introduction à la littérature fantastique. Paris: Seuil.)

52Todorov notes that the genres (and it can be assumed that he means theoretical as well as historical genres) do not exist in the literary works, but rather that they are manifested in them. According to Todorov, if a theory tries to explain it, the relationship of manifestation between genres and works is characterized by probability and cannot be seen as absolute (Todorov 1970, 26Todorov, Tzvetan. 1970. Introduction à la littérature fantastique. Paris: Seuil.). An important point can be derived from Todorov’s explanations: even historical descriptions of genres depend on theoretical presuppositions, or rather, different genre theories vary in the extent to which they integrate historical observations into their definitions of generic systems and genres. The debate about a system versus a history of genres can then be viewed as one of degree (from the extreme that history is not needed to establish a theory of genres to the other that a theory of genres is only possible in the description of historical circumstances) and terminology (are different kinds of genres, abstract-theoretical and historical ones, to be distinguished and which notion should be called a “genre”?).

53As was outlined in the previous chapter, the different genre theories that can be ascribed to the realistic side concentrate on different locations of the being of genres. The ones that see it as primarily determined by production would also need to focus on the productive side to describe genres historically, for instance, on the history of the creation and publication of the literary works that participate in the genres. In the same way, if genres are primarily conceptualized as a phenomenon of reception, the history of the reception of literary works that are seen as instances of the genres becomes a central element of the theory. Such a genre theory is, for example, sketched by the romance philologist Jauß. Croce’s rejection of genres as relevant concepts because every work of art is individual and violates genres is taken up by Jauß, who objects that a literary work can only be understood as breaking the rules of genres if there is a previous understanding of these rules: “it still presupposes preliminary information and a trajectory of expectations (Erwartungsrichtung) against which to register the originality and novelty” (Jauß 2014, 131Jauß, Hans Robert. 2014. “Theory of Genres and Medieval Literature.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 127–147. New York: Routledge.). The horizon of what can be expected is conceived as the contemporaneous reader’s knowledge of tradition and experience with other literary works. Because such a horizon of expectation is always present, there is no work without a genre. Because the horizon may be shifted with the experience that a reader makes with new works, genres have a “processlike appearance and ‘legitimate transitoriness’” (Jauß 2014, 131Jauß, Hans Robert. 2014. “Theory of Genres and Medieval Literature.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 127–147. New York: Routledge.). Jauß concludes that “literary genres are to be understood not as genera (classes) in the logical senses, but rather as groups or historical families. As such, they cannot be deduced or defined, but only historically determined, delimited, and described” (Jauß 2014, 131Jauß, Hans Robert. 2014. “Theory of Genres and Medieval Literature.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 127–147. New York: Routledge.). Because the readers’ horizon of expectation cannot be determined from a purely theoretical standpoint, Jauß’ genre theory is essentially historical. However, it is still a theory, especially when the approach is used to trace the history of one or several genres in broader lines:

the history of genres in this perspective also presupposes reflection on that which can become visible only to the retrospective observer: the beginning character of the beginnings and the definite character of an end; the norm-founding or norm-breaking role of particular examples; and finally, the historical as well as the aesthetic significance of masterworks, which itself may change with the history of their effects and later interpretations, and thereby may also differently illuminate the coherence of the history of their genre that is to be narrated. (Jauß 2014, 132Jauß, Hans Robert. 2014. “Theory of Genres and Medieval Literature.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 127–147. New York: Routledge.)

54Here, Jauß also recognizes that a specific literary work’s role in the history of a genre is not only determined by the contemporaneous context of reception but also depends on how broadly the temporal context is chosen and which perspective the scholar has on it. This view can as well be related to Hempfer’s constructivist synthesis: In this case, the normative facts are the expressions of horizons of expectations about genres, which must be substantiated through historical sources,48 and the genres are constructed in the interaction of the person with these facts.49

55Many more theoretical approaches to genres are concerned with determining trans-temporal basic genres. One example is Goethe’s attempt to define the epic, the lyric, and the drama as the three genuine natural forms (Genette 2014, 212Genette, Gérard. 2014. “The Architext.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 210–218. New York: Routledge.). Problems with the definitions of these three natural forms are pointed out by Genette, who introduces a more differentiated terminological system. It aims to clarify which aspects of the three basic forms can be considered trans-historical and which ones are historically bound. For Genette, the lyrical, epical, and the dramatic can be defined as “modes”, understood as linguistic categories that describe the mode of enunciation, for example, narration in the case of the epical and dramatic representation for the dramatic. On the other hand, as soon as thematic elements enter the concepts, Genette argues that they become historically variable. Only in this form, in combining formal and thematic elements and in pointing to specific historical conventions, should they be called “genres” (Genette 2014, 210, 213Genette, Gérard. 2014. “The Architext.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 210–218. New York: Routledge.). Even so, to do justice to the importance of the three major genres, lyric, epic, and drama, and the prominent status that they had in the history of literature, Genette calls them “archigenres”:

Archi-, because each of them is supposed to overarch and include, ranked by degree of importance, a certain number of empirical genres that – whatever their amplitude, longevity, or potential for recurrence – are apparently phenomena of culture and history; but still (or already) -genres, because (as we have seen) their defining criteria always involve a thematic element that eludes purely formal or linguistic description. (Genette 2014, 213Genette, Gérard. 2014. “The Architext.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 210–218. New York: Routledge.)

56Genette also attributes a dual status of higher-order categories and specific historically manifested genres to less prominent forms such as the novel or the comedy, which can be subdivided further into “species”, a concept which is comparable to subgenres, “with no limit set a priori to this series of inclusions” (Genette 2014, 213Genette, Gérard. 2014. “The Architext.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 210–218. New York: Routledge.). Although Genette separates a level of the trans-historical, linguistically defined modes, by admitting a dual status for genres, he maintains a double function of generic terms as theoretical and historical entities, and is inclined towards the theoretical status:

There is no generic level that can be decreed more ‘theoretical’, or that can be attained by a more ‘deductive’ method, than the others: all species and all subgenres, genres, or supergenres are empirical classes, established by observation of the historical facts or, if need be, by extrapolation from those facts – that is, by a deductive activity superimposed on an initial activity that is always inductive and analytical (Genette 2014, 214Genette, Gérard. 2014. “The Architext.” In Modern Genre Theory, edited by David Duff, 210–218. New York: Routledge.)

57If no generic level can be decreed more theoretical than others, they are all theoretical, although empirically induced. Compared to the production- or reception-aesthetic and the social- and function-historical-oriented approaches on the one side and the essentially literary-theoretical positions on the other, the semiotic models of genres and generic terms as elaborated, for example, by Raible and Schaeffer can be located on a middle position regarding their systematic and historical conception of genres. They are based on a theory of language and on models of the discursive levels that are involved in speech acts, which forms their theoretical core. History enters into this system because the meaning of signs is context-dependent and changes over time. In addition, the speech act is embedded into a situational context. Because there are a speaker and a hearer, or an author and a reader, not only the linguistic but also the extra-linguistic context becomes relevant, although this aspect is not the primary concern of the semiotic approaches.

58In its applied form, digital genre stylistics deals with corpora of contemporary or historical texts and has, therefore, a strong empirical foundation. Historical realizations of literary works are at the center of digital text analysis. Para-textual and extra-textual factors are often included in an analysis as metadata. For example, genre labels of different proveniences are included, as well as biographic information about the works’ authors, information about how the works have been received and valued by contemporaries or literary critics, or details about the sources of the texts and their publishing (when were the works published, where and by whom?). However, a broader or closer consideration of the literary and extra-literary-historical context is usually not pursued as part of the quantitative digital genre analysis itself. One example is Underwood, who places his analysis of detective, science fiction, and Gothic novels in the context of the history of reception. He uses basic bibliographic metadata to do so, but not entire historical documents, which could serve to reconstruct how the works in question and the genres they are associated with were received in their time (Underwood 2016, 2, 11, 17, 20–21Underwood, Ted. 2016. “The Life Cycles of Genres.” Journal of Cultural Analytics 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.22148/16.005.). The approach is reasonable because supervised learning is used, and if genre assignments are the target categories, they need to be formulated as compact terms. However, the idea of relating the analysis of the texts to how they were received in terms of genre historically is there. In most corpus-based analyses, though, no shifts in the relationship between generic terms and texts are analyzed, but one specific synchronic view. The synchronic view may either be based on scholarly and librarian classifications, on those made by contemporary readers, publishing houses, or booksellers, or on labels found on historical editions of the texts.50 The first group of contemporary labels thus leads to an analysis of how today’s genre concepts relate to the style of historical texts and, depending on the kind of textual material that is analyzed – twentieth-century or seventeenth-century texts, for instance – the contexts of production and reception are quite different. In the latter case of using historical genre labels, a specific historical section of the literary field is analyzed, and the contexts of the texts themselves and their generic categorization are congruent. Even if the historical development of genre concepts is not explicitly modeled from the point of view of reception over time, quantitative genre stylistic analyses are likely to involve different relationships between genre labels and texts, especially if the corpora are very large and comprise texts of one long or of several literary-historical periods. In the end, macroanalytic and, thus also, diachronic studies are enabled by the availability of a huge number of literary texts in digital format.51

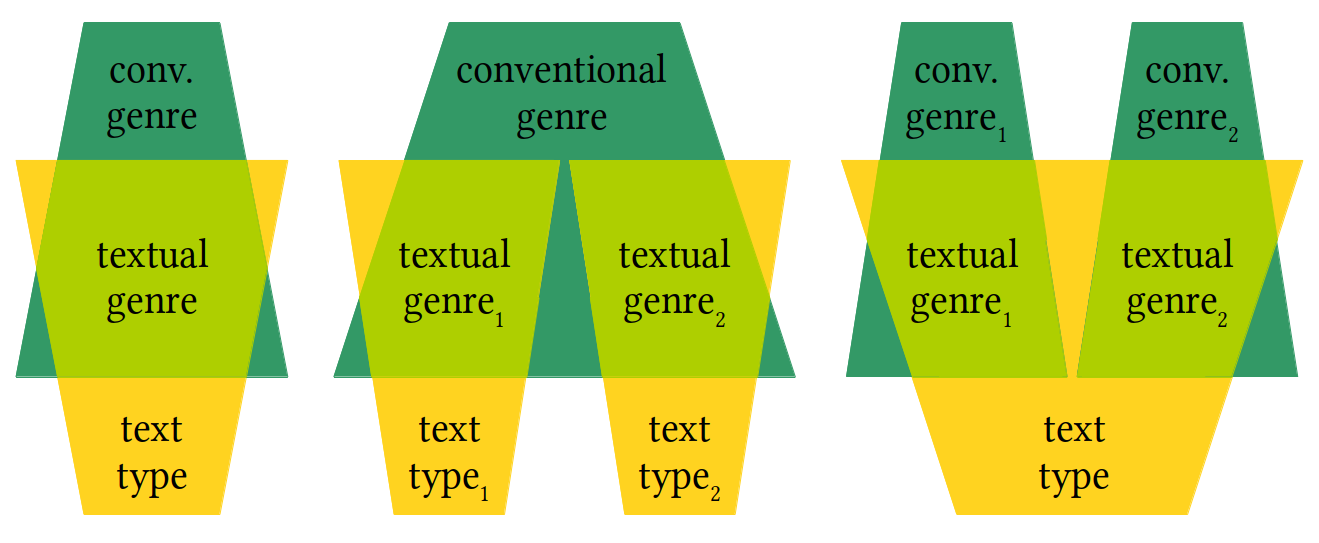

59Digital genre stylistics can thus refer to both systematic and historical concepts of genre. An important question is whether one can speak of literary genres in the same sense for the text groups constituted or characterized by digital text analyses as is done in traditional literary genre studies. This thesis argues that literary theory's notions of genre are not directly transferable to digital genre stylistics, and that the field needs its own conceptual set with which to meaningfully describe its questions, methods, and results. Such a conceptual set also has the task of clarifying the relationship to existing concepts from other fields, that is, especially literary studies, linguistics, computational linguistics, and computer science. In the following, existing conceptual systems on textual and communicative, theoretical and historical dimensions of genre are discussed, and a conceptual system of our own for digital genre stylistics is proposed.

60In digital genre stylistics, it has sometimes been proposed that one should not speak about the analysis of “genres” in this case, but of “text types”. This is because of the focus of digital genre stylistics on the literary texts themselves and more specifically on their linguistic surface and style, and the relatively limited inclusion of information that is related to the literary-historical and social context. At the same time, genre is a concept that appears to be strongly influenced also by extra-textual historical factors. On the one hand, the terminological distinction between genres and text types has its origin in linguistics, where literary genres are differentiated from linguistic text types. On the other hand it has also been proposed in literary genre theory itself as a means of distinguishing between genres that are based purely on textual and linguistic criteria and historical genres. This is similar to Genette’s proposal to differentiate between mode and genre. In the context of text linguistics, text types (in German, “Texttypen”) are described as follows:

Texte werden zu Texttypen zusammengefasst auf der Grundlage linguistischer Kriterien. Texttypen verlaufen quer zu den Textsorten in verschiedenen Kommunikationsbereichen. Als linguistische Kriterien gelten dabei textinterne Merkmale (Merkmale der Textinfrastruktur) wie Stil (Stiltyp, z.B. Ironie, Nominalstil), Medialität (medialer Typ, z.B. digitaler Text, konzeptionell mündlicher Text), Textfunktion auf der Basis sprachlicher Indikatoren (Funktionstyp, z.B. Kontakttext), Themenentfaltung/Vertextung (Vertextungstyp, z.B. explikativer Text). (Gansel 2011, 13Gansel, Christina. 2011. Textsortenlinguistik. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.)

61Style is directly mentioned as a defining characteristic of text types in the linguistic sense. However, the linguistic term that is used in a way that can be compared to the general conception of literary genres is also “text type” (in German, “Textsorte”):

Wir definieren Textklasse als das Vorkommen einer Menge von Texten in einem abgegrenzten, durch situativ-funktionale und soziale Merkmale – also textexterne Merkmale – definierten kommunikativen Bereich, in dem sich Textsorten ausdifferenzieren. [Z. B. Textklasse] Religion – [Textsorten] Predigt, Ordensregel, Enzyklika oder [Textklasse] Politik – [Textsorten] Koalitionsvertrag, Parteiprogramm, Regierungserklärung. (Gansel 2011, 12–13Gansel, Christina. 2011. Textsortenlinguistik. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.)